Expert Insights on Elevating Middle School Literacy

The demand for innovative and engaging curricula is at an all-time high. Recognizing this urgent need, Lavinia Group has introduced its groundbreaking RedThread Knowledge Middle School ELA...

The brain isn't wired to read, not without explicit, step-by-step instruction. Most children require reading instruction in phonics, vocabulary, and background knowledge to comprehend the written word.

In an effort to equip teachers with a clear path to impactful literacy pedagogy, the National Reading Panel distilled five essential pillars of teaching reading:

The science of reading takes a structured approach to teaching reading with phonics instruction as a foundational element. But, teaching literacy using the science of reading involves much more than just phonics. and at times, some have used these terms interchangeably.

It goes without saying that if you can’t read the words in front of you, comprehension is an impossible task.

This happens, at least in part, due to the frequent and understandable confusion between phonemic awareness and phonics skills–the former concerned with the sounds of words and the latter referring to the visual and auditory relationships between letters and sounds.

Establishing phonemic awareness happens before phonics instruction, and for good reason. Students must first hear and identify sounds before connecting them with letters and letter combinations.

Adding to this conversation, Dr. Bruce McCandliss, head of the Educational Neuroscience Initiative at Stanford University, published a study confirming that beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships (phonics) instead of learning whole words increase brain activity in the area best wired for reading.

The study demonstrated that words learned through letter-sound instruction elicit neural activity biased toward the left side of the brain, which encompasses visual and language regions. Words learned via whole-word association showed activity biased toward right-hemisphere processing. Strong left-hemisphere engagement during early word recognition is a hallmark of skilled readers and is characteristically lacking in children and adults who struggle with reading.

So why does phonics get all the attention?

According to Dr. Jack Smith, former Superintendent of Schools, Montgomery County Public Schools, "I think because it's the most obvious and because if you miss that part, you miss the rest of it. We pay attention to the beginning of the journey, the actual learning of the sound-letter relationship, because that's the start of learning to read, and it's more straightforward. You can hear it. You can't hear a lack of comprehension. Phonics, one of the first steps to reading, is absolutely essential and necessary. It is not, however, sufficient to become an independent reader."

As students master phonics, teachers should also prepare them for fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

"Most people don't understand what fluency is," says Dr. Smith, "and so, they don't realize that because the child reads slowly, that really can interrupt comprehension. Well, they can't really tell from the outside if comprehension strategies are being taught, if fluency strategies are being taught, if kids are being taught more vocabulary, if phonemic awareness has been built into the kid's life, both in early learning and in their home and community life. But they can tell if someone has sat there and said, 'This is a B, it says ‘buh.'"

A critical point about reading comprehension is its close correlation with prior content knowledge. Two studies conducted over 50 years apart (Frederick Bartlett’s 1932 Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology, and Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie's 1988 Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers' memory of text) demonstrated that students tested better on comprehension of reading material that they found culturally relevant or in which they had a deeper background or greater interest–regardless of how their reading skills were measured by other metrics.

Structured literacy, an instructional approach aligned with Science of Reading research, emphasizes highly explicit and systematic teaching of all important literacy components. These components include both foundational skills (e.g., decoding, spelling) and higher-level literacy skills (e.g., reading comprehension, written expression).

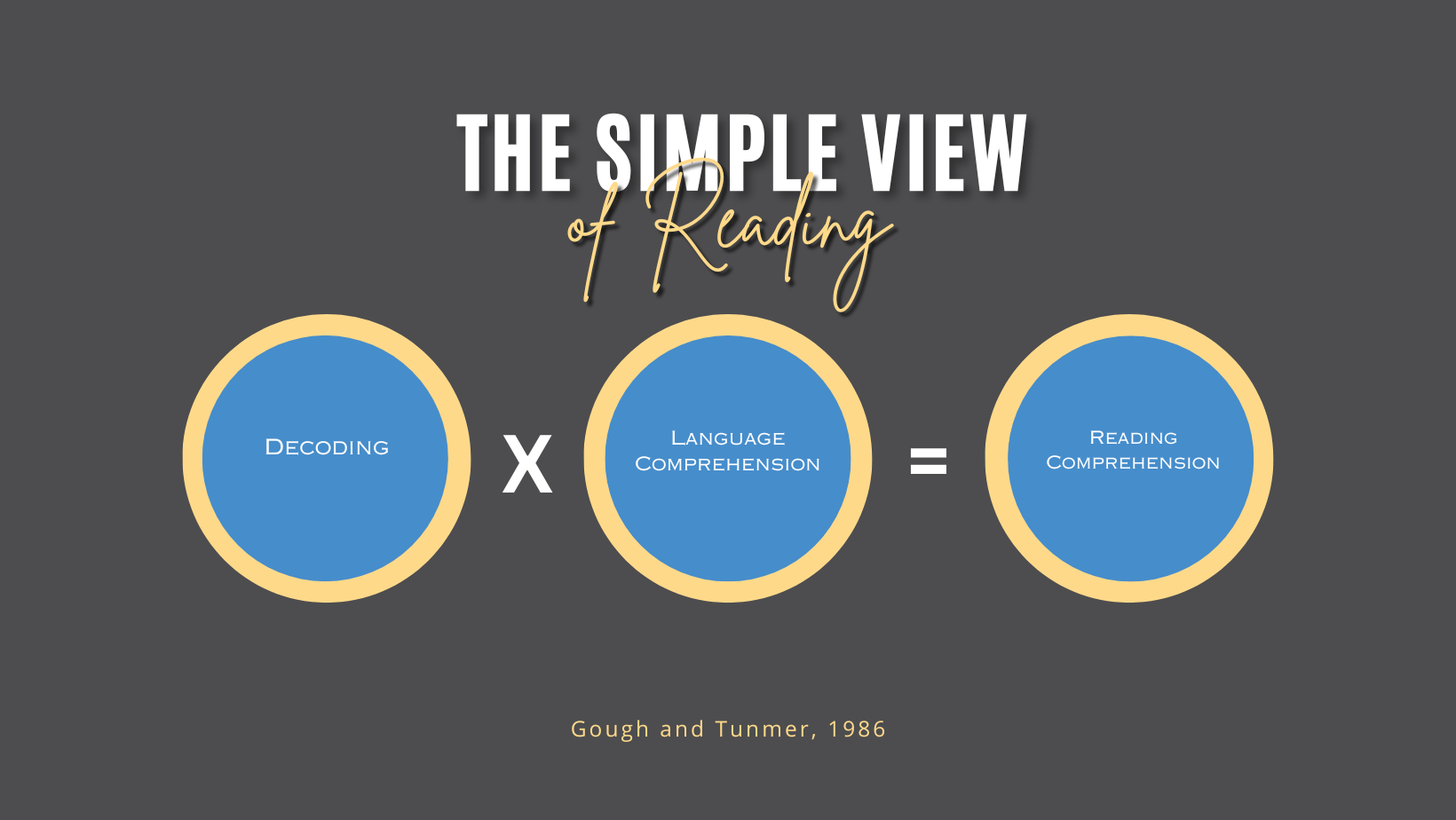

Structured Literacy incorporates explicit, systematic phonics into literacy instruction. Philip B. Gough and William E. Tunmer’s research (The Simple View of Reading) has contributed greatly to our understanding of the most effective ways to teach reading. If children cannot encode and decode naturally, Gough and Tunmer show that exposure to unfamiliar text will only lead to practicing compensatory strategies (such as relying on picture cues), while valuable instructional time passes by.

Explicit instruction in fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension is necessary for successful readers to acquire and integrate all five fundamentals of the science of reading.

"There's a tipping point at which someone becomes an independent reader," Dr. Smith explains. "There's a point where we recursively teach ourselves to read, we teach ourselves vocabulary, through context, looking it up. Even in upper elementary, middle, and high school, students are learning about reading. You're going to get explicit instruction in vocabulary and reading comprehension strategies. We teach those because those are ultimately ways of understanding the language at the most complex level."

With their 1986 study, The Simple View of Reading, Gough and Tunmer challenged the hierarchical thinking that prioritized either decoding or comprehension as a higher priority over the other rather than as interdependent skills that combine to build reading comprehension. Decoding and listening comprehension each involves a wide array of skills and knowledge.

The Simple View of Reading, itself, doesn’t provide sufficient guidance for the development of instructional strategies that develop and grow reading comprehension skills; however, it offers two broad areas of focus that are proven to affect a student’s ability to comprehend text.

Hollis Scarborough introduced the Reading Rope model in 1992 as a way to visualize The Simple View of Reading.

A double braid of colored pipe cleaners expands The Simple View into two strands of a rope: Language Comprehension and Word Recognition. Each strand is made of individual threads to show the many individual skills needed within the two larger strands. For teachers of English reading, this is a visual reminder of the complex components for reading and the number of things that must be taught to achieve success.

By adopting a comprehensive approach to reading instruction, we give all children a much greater chance to succeed through improved reading skills, better reading comprehension, and increased motivation to read. Dr. Smith concludes:

"It's not just about the methodology. It's not just about the strategy. It is the fundamentals of the Science of Reading that are critically important. But don't forget the second half: after phonemic awareness and phonics fluency, comprehension and vocabulary and understanding the most nuanced levels of reading complex fiction and nonfiction are just as critically important."

Decades of research have reinforced the importance of aligning literacy instruction programs with the Science of Reading, yet the debate continues. As we face the realities of achievement disparity, it's more important than ever to transform literacy instruction strategies from balanced literacy to structured literacy and guided reading to small-group instruction. Phonics has its place, yet we must prioritize the Science of Reading as a more comprehensive approach.

The demand for innovative and engaging curricula is at an all-time high. Recognizing this urgent need, Lavinia Group has introduced its groundbreaking RedThread Knowledge Middle School ELA...

[EAGAN, MINN.]— Lavinia Group, a division of K12 Coalition, rolls out its expanded suite of professional learning opportunities for the upcoming 2024-2025 school year. Educators will refresh their...

How hard would it be to climb Mount Everest…blind? Particularly if you wanted to try something new but weren’t confident in your abilities yet.